PPIs Linked to Pancreatic Cancer, Death

Studies stoke debate over safety of the reflux drugs

New data are yet again casting a shadow over the safety of proton pump inhibitors.

In one study, presented at this year’s Digestive Disease Week (abstract Su1268), researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that PPIs were linked to an increased risk for pancreatic cancer. A second study published in the BMJ Openreported that military veterans who used PPIs had a small but significantly increased risk for premature death compared with those who took other reflux drugs or no such therapy.

Pancreatic Cancer Link

“There’s a lot of laboratory data to suggest links between the trophic hormone gastrin and abnormal cell growth of various types, and one key medication known to cause gastrin elevation is [the] PPI,” said Malcolm Kearns, MD, a resident in internal medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia, who helped conduct the study looking at pancreatic cancer.

“The number of prescriptions for PPIs has skyrocketed in recent years—many are started and continued without appropriate indications or regular evaluation. So we wanted to examine at a population level whether there was an association between pancreatic cancer and PPIs,” he said.

PPIs cause hypergastrinemia, which has been tied to gastrointestinal malignancies in experimental models. So the Penn researchers sought to evaluate the relationship between PPIs and pancreatic cancer, as well as survival after diagnosis of the disease.

The researchers used the Health Improvement Network, a medical records database representative of the U.K. population, to conduct a nested case–control study and a retrospective cohort study. The case–control study matched patients with incident pancreatic cancer with up to four controls based on age, sex, practice site, and duration and calendar time of follow-up. The researchers estimated odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals for the association between use of PPIs and pancreatic cancer.

In the retrospective cohort study, the researchers compared the survival of pancreatic cancer patients according to how long they had been taking PPIs at the time they were diagnosed.

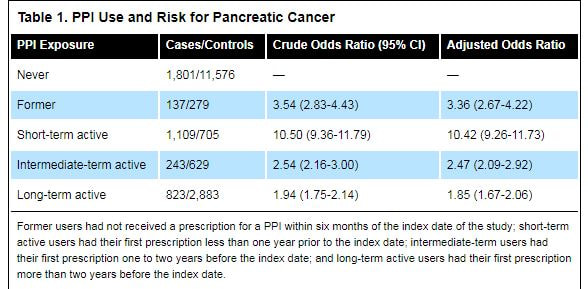

In total, the researchers analyzed 4,113 patients with pancreatic cancer and 16,072 matched controls. They found that cancer patients were more likely to be current PPI users at the time of the study (53% vs. 26%). These patients also were more likely to be obese, to smoke, to use alcohol and to have diabetes. Compared with controls, duration of PPI use was found to be significantly lower in pancreatic patients (2.47 vs. 4.14 years; OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.83-0.87). After adjusting for body mass index, smoking, alcohol use and diabetes, both active and former PPI users had an increased risk for pancreatic cancer, the investigators found (Table 1).

In one study, presented at this year’s Digestive Disease Week (abstract Su1268), researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that PPIs were linked to an increased risk for pancreatic cancer. A second study published in the BMJ Openreported that military veterans who used PPIs had a small but significantly increased risk for premature death compared with those who took other reflux drugs or no such therapy.

Pancreatic Cancer Link

“There’s a lot of laboratory data to suggest links between the trophic hormone gastrin and abnormal cell growth of various types, and one key medication known to cause gastrin elevation is [the] PPI,” said Malcolm Kearns, MD, a resident in internal medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia, who helped conduct the study looking at pancreatic cancer.

“The number of prescriptions for PPIs has skyrocketed in recent years—many are started and continued without appropriate indications or regular evaluation. So we wanted to examine at a population level whether there was an association between pancreatic cancer and PPIs,” he said.

PPIs cause hypergastrinemia, which has been tied to gastrointestinal malignancies in experimental models. So the Penn researchers sought to evaluate the relationship between PPIs and pancreatic cancer, as well as survival after diagnosis of the disease.

The researchers used the Health Improvement Network, a medical records database representative of the U.K. population, to conduct a nested case–control study and a retrospective cohort study. The case–control study matched patients with incident pancreatic cancer with up to four controls based on age, sex, practice site, and duration and calendar time of follow-up. The researchers estimated odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals for the association between use of PPIs and pancreatic cancer.

In the retrospective cohort study, the researchers compared the survival of pancreatic cancer patients according to how long they had been taking PPIs at the time they were diagnosed.

In total, the researchers analyzed 4,113 patients with pancreatic cancer and 16,072 matched controls. They found that cancer patients were more likely to be current PPI users at the time of the study (53% vs. 26%). These patients also were more likely to be obese, to smoke, to use alcohol and to have diabetes. Compared with controls, duration of PPI use was found to be significantly lower in pancreatic patients (2.47 vs. 4.14 years; OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.83-0.87). After adjusting for body mass index, smoking, alcohol use and diabetes, both active and former PPI users had an increased risk for pancreatic cancer, the investigators found (Table 1).

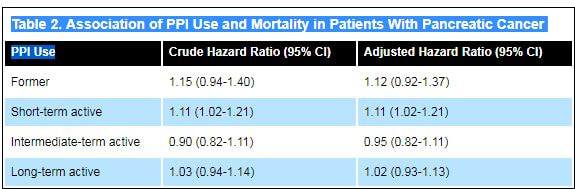

The researchers also found “a modest decrease” in survival after diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in short-term, active PPI users, defined as having received their first PPI prescription less than 12 months before starting the study (Table 2).

Philip Katz, MD, director of Motility Laboratories for the Division of Gastroenterology at the Jay Monahan Center for Gastrointestinal Health at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine, in New York City, called the study “well done and thoughtful.” But Dr. Katz objected to the conclusion that PPIs increased the risk for pancreatic cancer.

“A shorter duration of PPI use had a stronger association with pancreatic cancer compared to a longer duration, which speaks against the PPI being the issue,” Dr. Katz said. “One would suspect a confounder such as GERD, or that the patients’ symptoms were suggestive of an acid-related problem, but were likely from the cancer instead,” he said. “What this really reinforces, as do many studies like it, is that we shouldn’t be prescribing these drugs without a solid indication.”

Acknowledging this point, Dr. Kearns said, “What could have caused that increased odds ratio within six months [in short-term PPI users] could have been the symptoms of pancreatic cancer itself. But what we found compelling about our data was that the elevated OR was persistent even up to 24 months prior to diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.

“The reason that’s significant is that the mean survival following diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is around six months. So it would be unlikely that patients that were prescribed PPIs two years prior to diagnosis of pancreatic cancer were started on them because of symptoms of pancreatic cancer,” he said.

“[PPIs] are a medication that’s often prescribed and continued without giving it a great deal of thought,” Dr. Kearns added. “So I hope that our study at least makes somebody think twice about refilling a prescription, or think to ask their patient if they’re really benefiting from it or suggest trialing off of their PPI.”

Mortality Risk

In the BMJ study, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the VA St. Louis Health Care System looked at death rates among a massive cohort of male veterans, of whom roughly 350,000 had started taking a PPI or histamine H2 receptor antagonist between October 2006 and September 2008. Patients were on the medications for an average of approximately 5.7 years.

Men who took PPIs had a 15% increased risk for death during the study period compared with those who did not use the drugs. The increase was 23% when compared with use of neither a PPI nor an H2 blocker, according to the investigators.

The difference in mortality was greater for people who took a PPI without a recorded GI condition, the researchers reported, and it appeared to increase with duration of use.

“The results suggest excess risk of death among PPI users; risk is also increased among those without gastrointestinal conditions and with prolonged duration of use. Limiting PPI use and duration to instances where it is medically indicated may be warranted,” they wrote.

Amitabh Chak, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, in Cleveland, and an expert in GERD, said observational studies like the one in BMJ Open “should always be taken with a grain of salt and interpreted cautiously. They can be provocative but the results may be confounded by unmeasured risk factors.”

However, Dr. Chak, whose group recently received a $6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to study Barrett’s esophagus, said the findings “should help generate hypotheses and reconsider practices. These studies need to also be replicated, and often when the study is performed in another population, the results are contradictory.”

For example, a recent study in JAMA Neurology found that use of PPIs was associated with dementia (2016;73:410-416). But at least one subsequent prospective study failed to support that link (J Am Geriatr Soc. 7 June 2017. [Epub ahead of print]).

“So how should we interpret these results? PPIs clearly are beneficial in treating GERD, preventing bleeding from [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs], and eradicating Barrett’s esophagus in patients undergoing ablative therapy. We should use PPIs for patients who benefit from PPIs and need them. We should not use PPIs for patients who don’t benefit from their use.”

http://www.gastroendonews.com/In-the-News/Article/08-17/PPIs-Linked-to-Pancreatic-Cancer-Death/42170

“A shorter duration of PPI use had a stronger association with pancreatic cancer compared to a longer duration, which speaks against the PPI being the issue,” Dr. Katz said. “One would suspect a confounder such as GERD, or that the patients’ symptoms were suggestive of an acid-related problem, but were likely from the cancer instead,” he said. “What this really reinforces, as do many studies like it, is that we shouldn’t be prescribing these drugs without a solid indication.”

Acknowledging this point, Dr. Kearns said, “What could have caused that increased odds ratio within six months [in short-term PPI users] could have been the symptoms of pancreatic cancer itself. But what we found compelling about our data was that the elevated OR was persistent even up to 24 months prior to diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.

“The reason that’s significant is that the mean survival following diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is around six months. So it would be unlikely that patients that were prescribed PPIs two years prior to diagnosis of pancreatic cancer were started on them because of symptoms of pancreatic cancer,” he said.

“[PPIs] are a medication that’s often prescribed and continued without giving it a great deal of thought,” Dr. Kearns added. “So I hope that our study at least makes somebody think twice about refilling a prescription, or think to ask their patient if they’re really benefiting from it or suggest trialing off of their PPI.”

Mortality Risk

In the BMJ study, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the VA St. Louis Health Care System looked at death rates among a massive cohort of male veterans, of whom roughly 350,000 had started taking a PPI or histamine H2 receptor antagonist between October 2006 and September 2008. Patients were on the medications for an average of approximately 5.7 years.

Men who took PPIs had a 15% increased risk for death during the study period compared with those who did not use the drugs. The increase was 23% when compared with use of neither a PPI nor an H2 blocker, according to the investigators.

The difference in mortality was greater for people who took a PPI without a recorded GI condition, the researchers reported, and it appeared to increase with duration of use.

“The results suggest excess risk of death among PPI users; risk is also increased among those without gastrointestinal conditions and with prolonged duration of use. Limiting PPI use and duration to instances where it is medically indicated may be warranted,” they wrote.

Amitabh Chak, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, in Cleveland, and an expert in GERD, said observational studies like the one in BMJ Open “should always be taken with a grain of salt and interpreted cautiously. They can be provocative but the results may be confounded by unmeasured risk factors.”

However, Dr. Chak, whose group recently received a $6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to study Barrett’s esophagus, said the findings “should help generate hypotheses and reconsider practices. These studies need to also be replicated, and often when the study is performed in another population, the results are contradictory.”

For example, a recent study in JAMA Neurology found that use of PPIs was associated with dementia (2016;73:410-416). But at least one subsequent prospective study failed to support that link (J Am Geriatr Soc. 7 June 2017. [Epub ahead of print]).

“So how should we interpret these results? PPIs clearly are beneficial in treating GERD, preventing bleeding from [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs], and eradicating Barrett’s esophagus in patients undergoing ablative therapy. We should use PPIs for patients who benefit from PPIs and need them. We should not use PPIs for patients who don’t benefit from their use.”

http://www.gastroendonews.com/In-the-News/Article/08-17/PPIs-Linked-to-Pancreatic-Cancer-Death/42170